Is unsafe ...unsafe? Pt. 1

Unsafe package explained

This time I held a talk at Lviv Golang community event in Lviv, Ukraine.

I was talking about unsafe package and tried to answer how unsafe is unsafe package.

Unsafe package has a concise and descriptive name, which warns you even if you don’t know what possibilities this package provides and at what price. I love the name as it follows all recommendations from “Effective Go”. Actually, when using unsafe package we should strictly follow Go team’s documentation and recommendations. Here is the all the provided description for this package

“Package unsafe contains operations that step around the type safety of Go programs.”, golang.org

With a little warning:

“Packages that import unsafe may be non-portable and are not protected by the Go 1 compatibility guidelines”, golang.org

Functionality description looks very abstract, so let’s check out those “unsafe” operations:

func Alignof(x ArbitraryType) uintptr

func Offsetof(x ArbitraryType) uintptr

func Sizeof(x ArbitraryType) uintptr

type ArbitraryType

type Pointer

One of the types, ArbitraryType

“is here for the purposes of documentation only and is not actually part of the unsafe package”, golang.org

So there are only three functions and one type. As far as there isn’t much to deal with, let’s try to review this package. So we’ve got Go team’s documentation and the source code to start with. To decide what to begin with let’s recall one quote:

“Talk is cheap. Show me the code”, Linus Torvalds

Well, let’s get straight to the code…

But the first interesting thing related to

But the first interesting thing related to unsafe package is that it has no source code. I mean it has functions prototypes and types definitions but not their implementation: not in Go neither in Assembly languages.

The reason is, opportunities that unsafe package provides are not possible to reach using Go functionality, that is why this package is built-in and known to the compiler, it has .go file only for the documentation purpose.

That is the reason I have mentioned above that we should strictly follow Go team’s documentation and recommendations.

Let’s do that and start from the Sizeof function.

func Sizeof(x ArbitraryType) uintptr

receives some type and returns uintptr.

The name is descriptive: it implies that this function returns the size of something(size of some type). For ease of understanding let me bring some abstractions to visualize the action.

As we know, our Go programs use memory for many purposes, including the storage of variables. Let’s describe memory using the following labels:

🎁 - 1 byte of memory

📦 - 1 byte of memory that we use

🥡 - 1 byte of memory that we use, but it’s useless(we will review this later)

⬆️ - pointer to address in memory

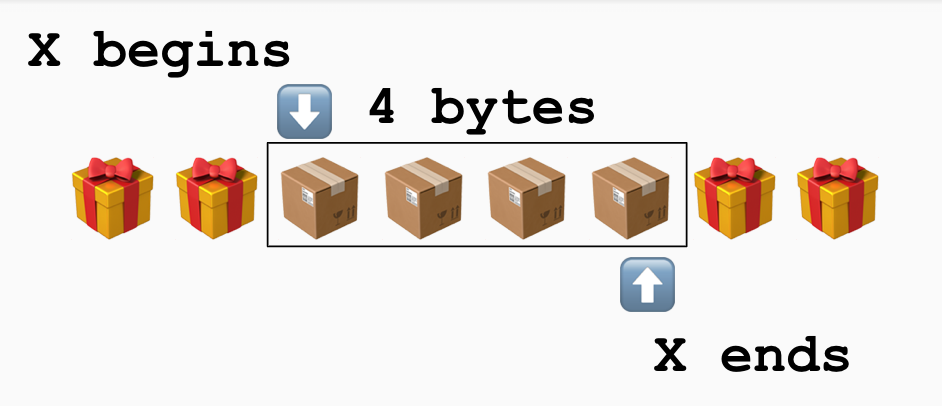

Using these labels let me get down to Sizeof mechanism: let’s review the next structure X

type X struct {

n1 int16

n2 int16

}

It will be placed in memory in the following way:

Struct X has 2 fields, each of them weights 2 bytes.

So the whole structure should weight: size(n1) + size(n2) + size(X) = 2 + 2 + 0 = 4. Nothing tricky here, so the next statement will be true:

unsafe.Sizeof(X) == 4 // true

func Offsetof(x ArbitraryType) uintptr

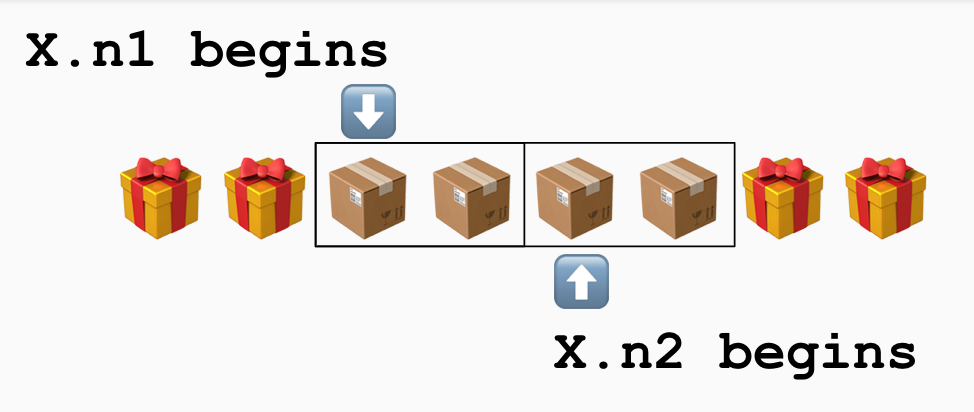

This one is a bit more complex, it has the same signature and returns offset. Let me show the mechanism using labels:

We have the same structure X with the same fields(same names and types)

type X struct {

n1 int16

n2 int16

}

You already know how it will be placed in memory, but this time let’s see how many bytes each field will take. It will be placed in memory in the following way:

It’s not hard to guess how those 2 fields will be placed in memory: the first one, X.n1, takes the first 2 bytes and the second one, X.n2, takes the following 2 bytes of memory.

Both next statements will be true:

unsafe.Offsetof(X.n1) == 0 // true

unsafe.Offsetof(X.n2) == 2 // true

func Alignof(x ArbitraryType) uintptr

This one is the most interesting because for the full understanding you have to know what alignment is. In plain words, it’s the way of placing data in the memory, so it can be accessed much faster.

This function returns the required alignment for the type of passed variable.

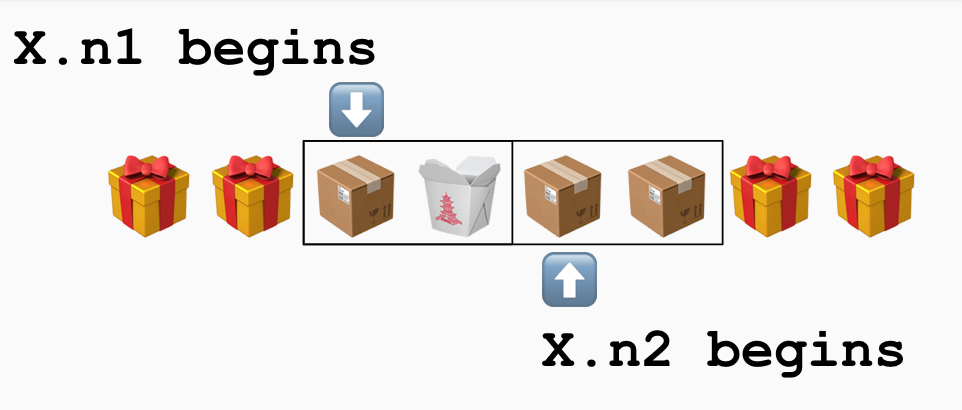

Let’s take structure X from the previous example and change it a bit:

type X struct {

n1 int8

n2 int16

}

now, n1 is int8. What will it change? To understand why alignment is important let’s check other metrics of X, for example, let’s check Sizeof.

Since one of the fields, n1 changed its weight from 2 bytes to 1 byte it’s legal to say that the size of struct X has changed too. So can we say that: size(X) = size(n1) + size(n2) = 1 + 2 = 3 is true?

…

Nope. The reason for that is alignment.

Let’s check how the new version of struct X is placed in the memory:

Because of the alignment field n2 can’t start from byte 2 and starts from byte 3 because of its weight.

Field of the size 2 can start only from memory address that is the result of multiplication of variable type size by some integer number: size(n2) * x = memory address.

So n2 can start from byte 0 or byte 2 but not from byte 1 or byte 3. Ok, but what if we will change the order of fields in struct X, so n2 will start from byte 0 and n1 from byte 3.

The size will be the same and the reason is alignment, again. We need to align the whole structure in memory so the size of the structure will be multiplications of the biggest Alignof(X.field).

That means that structure consist of multiple blocks of the same size and the size of one block is the biggest result of Alignof amongst all fields of that struct.

This knowledge can show us the way to minimize the memory usage of structures. Check this code snippet:

type First struct {

a int8

b int64

c int8

}

type Second struct {

a int8

c int8

b int64

}

fmt.Println("Big brain time: ", unsafe.Sizeof(First{}) == unsafe.Sizeof(Second{}))

They have different sizes because struct First uses 3 blocks by 8 bytes: Sizeof(First.a) + 7 padding bytes + Sizeof(First.b) + Sizeof(First.c) + 7 padding bytes = 24 bytes.

But struct Second uses only 2 blocks by 8 bytes: Sizeof(First.a) + Sizeof(First.c) + 6 padding bytes + Sizeof(First.b) = 16 bytes.

Use this knowledge next time you will create new structure 🙂.

This is the snippet with usage for all reviewed functions:

var x struct {

a int64

b bool

c string

}

fmt.Println("Size of x: ", unsafe.Sizeof(x))

fmt.Println("Size of x.c: ", unsafe.Sizeof(x.c))

fmt.Println("Alignment of x.a: ", unsafe.Alignof(x.a))

fmt.Println("Alignment of x.b: ", unsafe.Alignof(x.b))

fmt.Println("Alignment of x.c: ", unsafe.Alignof(x.c))

fmt.Println("\nOffset of x.a: ", unsafe.Offsetof(x.a))

fmt.Println("Offset of x.b: ", unsafe.Offsetof(x.b))

fmt.Println("Offset of x.c: ", unsafe.Offsetof(x.c))

Check the code out in the playground

All 3 reviewed functions work in the compile-time. It means that they will work properly when your program is launched/in run-time or will return an error when you try to compile your program.

But our next guest is much more unpredictable, it can crash the program in run time too.

Read about unsafe.Pointer and common issues with unsafe in the second part.